The Riotte Kerosene Bicycle Motor

While I’m working out the plot for my new book, I’m also trying to figure out what exactly the machine my heroine’s father has invented looks like. I have in mind for it to be an early motorcycle, but my knowledge of motorcycles and motors past and present is minimal. Fortunately my reliable friends at Google have scanned in volume 1 of The Horseless Age, a publication for the nascent automotive industry in 1895. There are a great many bicycle, tricycle and carriage motors described, from steam-powered to gasoline, and spring-motors, which were coiled by a hand-crank and then powered a bicycle for 15 miles. I was briefly excited by the description of an ether-motor–more efficient and powerful than using water for steam–until I looked a little further and learned that ether is extremely explosive, which is why we don’t see it used as a propellant in many engines these days. There will be some mishaps in the novel, but not the explosion and full-body burns sort of disaster.

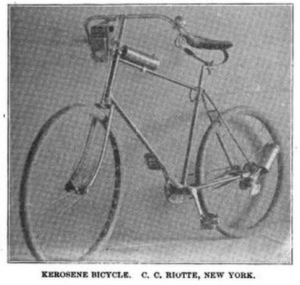

Right now the leading contender for me to base my fictional motorcycle off of is a kerosene motor, a lightweight option which could be attached to a regular bicycle frame. It doesn’t seem to have caught on, as the only mention I can find is this description on page 19 of Vol. 1, No. 1 of The Horseless Age, printed in November 1895.

The Riotte Kerosene Bicycle

C.C. Riotte, of the Riotte & Hadden Mfg. Co., 462 East 136th St., New York, has invented a kerosene motor for bicycles which is extremely simple, light and inexpensive. It can be attached to any ordinary bicycle, detached at a moment’s notice, and is started and stopped by a small handle at the oil tank. It consists of two small valves, a cylinder, piston and igniter.

The operation of the motor it [sic] as follows: When the piston descends, a cylinder full of air mixed with a small quantity of kerosene oil is compressed into the explosive chamber and there ignited by an electric spark which is generated from a small battery weighing one half pound. This battery never polarizes or requires recharging.

The air in the cylinder being highly heated from the combustion of oil drives forward the piston which is connected through a crank with the rear wheel as seen in the illustration. The operation continues on, almost noiseless and without smell, with every turn of the rear wheel. A speed of twenty five miles per hour has been attained with it on level ground and a pretty good speed maintained on grades of about four or five per cent.

The weight of the motor including tank full of oil is nine and one half pounds. The tank holds enough oil to carry a person 75 miles and when the oil gives out a quart of kerosene or any kind of petroleum lamp oil can be bought at any country store or of any farmer.

Mr. Riotte has been experimenting in gas and oil engines all his life, and has had a good deal to do with stationary and marine engines of all descriptions.

The principle of this bicycle motor is the same as that of his new improved stationary oil engines except that heavy weights and the fly wheel are dispensed with.

The firm is also constructing a carriage, which is propelled by a kerosene motor the same in principle as their stationary motors. The operating gear will have but one lever to start, stop, reverse, or go at any speed from 2 to 25 miles per hour. They expect to form a company to manufacture bicycle and carriage motors on a large scale.

As far as I can tell, it seems like a pretty plausible option, especially with the option to buy fuel on the road. One of the things I’ve realized about the development of motor vehicles is that they were initially hampered by the lack of infrastructure. To be successfully used for long distance travel, they needed to have good roads for all the wheeled vehicles, and for the fueled vehicles, they needed places to buy fuel. I’ve pretty much taken the existence of gas stations for granted, but now I assume that part of what made or broke the different motor options described in The Horseless Age was the availability of their required fuel, whether it was kerosene, ether, or gasoline. It may also explain the interest in the spring motors!