Dishes of the Peoples of Yakutia

I am prepping for NaNoWriMo, as I may have mentioned, and I am super excited about it, because I’m planning an epic fantasy set in something like Siberia/the Russian Far East, except there is magic around, and the indigenous peoples have the political cooperation and shamanistic powers to drive back the Cossacks instead of becoming a fur-producing colony for the Russian Empire.

As such, I’ve been reading about Siberian history, and the mythology of various peoples of the RFE, making good use of my Russian degree. I’ve always been interested in RFE history, since it’s only a hop, skip, and a jump from Alaskan history, so I have some seemingly random references that are suddenly helpful, like this cookbook. Why do I have “Dishes of the Peoples of Yakutia”? No idea. But now it is providing me with helpful information on the diet of the Sakha [Yakuts], Evens, Evenks, Yukaghirs, and Chukchis. I started with Chukchis, because I’ve been reading some of Waldemar Bogoras’s texts on the Chukchi. Here’s my own rough translation of this cookbook’s Chukchi section, with occasional personal commentary in italics. The Russian text happens to be online already. I should note that the authors say there are few Chukchi around in Yakutia (I believe they mostly live in the next region over, Chukotka), and therefore their recipes are all sourced from other publications.

Chukchis hunted for wild reindeer, marine mammals, wild fowl and other game. They also fished, gathered wild berries, edibles plants and their roots. They boiled or roasted meat and fish, but also dried many products.

- Pal’gyn [Пальгын] – Fat skimmed off of crushed and boiled reindeer bones, mixed with minced greens or boiled willow leaves and sorrel. Also mixed with meat for a smoked reindeer sausage.

- Vil’mulimul’ [Вильмулимуль] – Reindeer blood, kidney, liver, ears, roasted hooves, and lips mixed with berries and sorrel and stuffed into a stomach, which is dried and then saved in cold storage and fermented over winter to provide a rich spring food, full of calories and vitamins. This food is made by many northern peoples.

- Kykvatol’ [Кыкватоль] – Reindeer meat dried during windy weather in summer, or in the smoke indoors in wet weather. Outer layer is dry, but the interior remains fresh. It is sliced before eating, and fried if there are raw sections.

- Nuvkurak [Нувкурак] – Whale meat dried until it has a hard crust while the inside of the meat remains raw. This is boiled in large cauldrons and stored in jars of seal oil. This is only used during winter. I was recently reading The Shaman’s Coat by Anna Reid, who mentions that boiled whale meat was quite succulent.

- Mantak (or Intilgyn) for future use [Мантак (или интилгын) впрок] – Chukchis, as well as eskimos, widely used whale meat and whale skin [blubber?]. Blubber with tallow was eat raw and boiled. It was boiled for future use, and stored in jars with water and leaves of fireweed. This was a winter food. The leaves provided a pleasant smell and helped it keep longer. At the first frost in the fall, fresh blubber with tallow was put in a pit for meat. [This is a reasonable storage option in regions with permafrost.] Here it stayed until spring. In the winter it was eaten frozen, before bed. It was eaten boiled with a porridge made of the kyiugak plant.

- Dish of roots of grasses or herbs [Блюда из корней трав] – Peeled and washed roots and stems of edible plants are minced and then pounded into an evenly mixed mass then mixed with finely chopped reindeer meat and seal oil. This is a stand alone dish, but can be eaten with other dishes.

- K’uvykhsi [К’увыхси] – The upper stem and leaves of [three-wing-fruit] are gathered before it flowers and saved for later. The grass is boiled, cream scalded… too many exotic words in this one, but it is added to all traditional dishes.

- Fermented reindeer [Квашеные оленина] – Layers of reindeer meat and bones are tightly packed into a bag of either seal or reindeer skin, called a tenegyn. In this summer, the tenegyn is buried near any remaining patches of snow, and snow piled on top. In the winter the preserved meat is dug up.

- Fermented heads [Квашеные головы] – In mid-summer, when salmon first return, they begin to ferment the heads of these fish. First they make a small hole, taking up sod/turf from the earth. The hole is prepared for the heads. The bottom is covered with willow switches or sod, and on top of this a layer of fish spines. The heads are placed on the spines. Then the heads are covered with another layer of spines and on that, sod. They put earth over this and lightly tamp it down. Later, when the earth settles to be level with the sod, they take the heads out of the pit. Fermented heads are calculated to be ready in September, for the arrival of those who went far away for work. Apparently fermentation in plastic bags or buckets leads to botulism, while the traditional methods are safer.

- Boiled meat [Мясо отварное] – Reindeer meat is cut into small chunks. As many chunks as needed for a portion are put into a pot. Boil until ready: leave it a little under-cooked otherwise the reindeer loses its juiciness and the taste peculiar to this animal. Salt to taste. Remove the cooked meat from the broth and cut into small pieces. Pour broth over meat and serve.

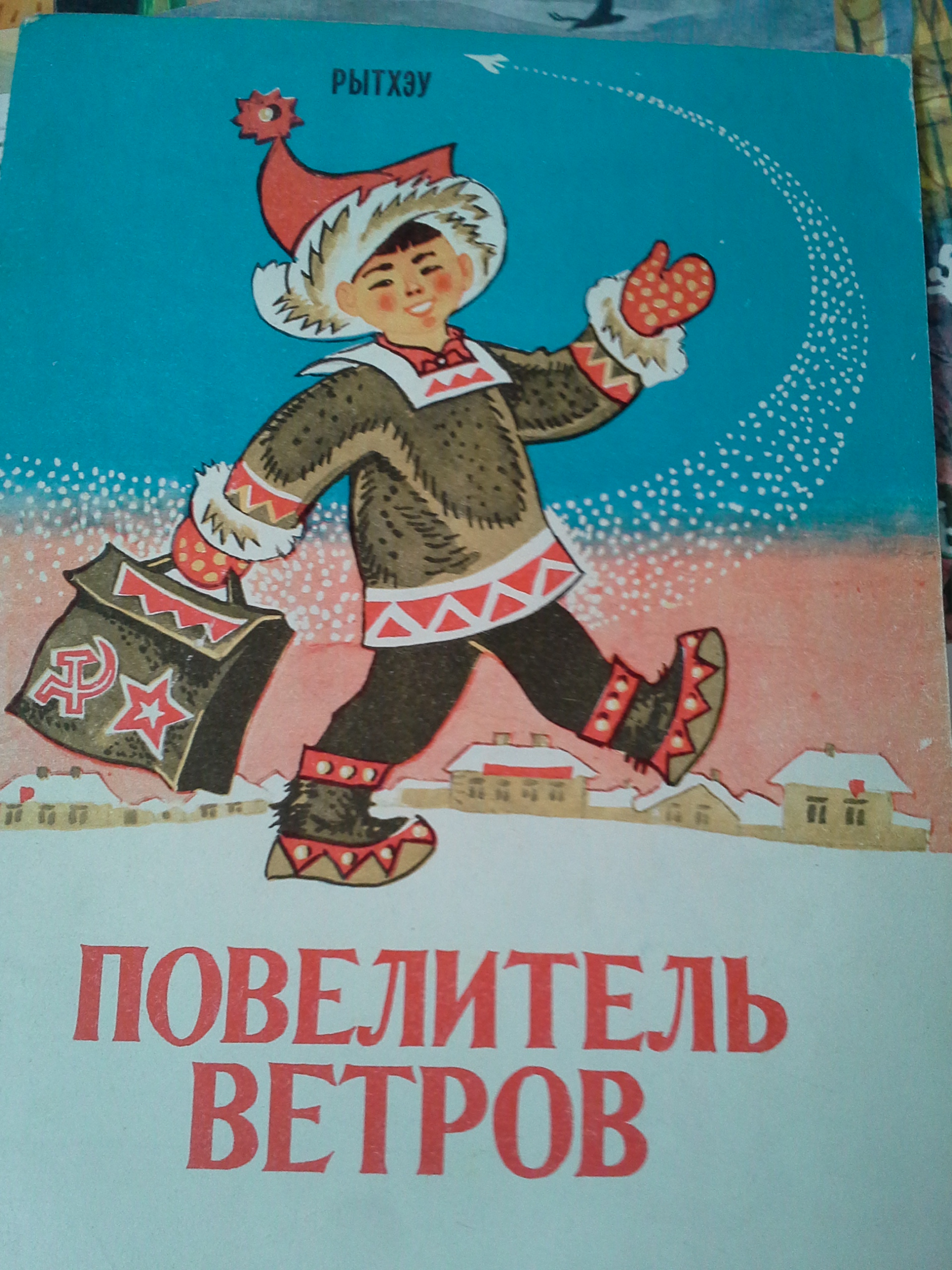

I think I have literally had this

Russian dictionary for fifteen years.

Perhaps next time I’ll share the dishes of the Yukhagirs, one of which is a cold drink made of whitefish caviar.

Apparently reading Russian language sources for my current project is the reason why I acquired US Dept. Of the Interior Fish & Wildlife Service Circular 43, “Glossary of Marine Conservation Terms in English and Russian,” compiled in 1956, and “My Nose Is Frostbitten: Useful Phrases for Russian-American Exchanges” by Melissa Chapin, even though neither or them can tell me what трехкрылоплодный горец is. Etymologically, I think it breaks down to three-wing-fruited mountaineer, which doesn’t help me place it in English. Apparently I need a botanical glossary as well!